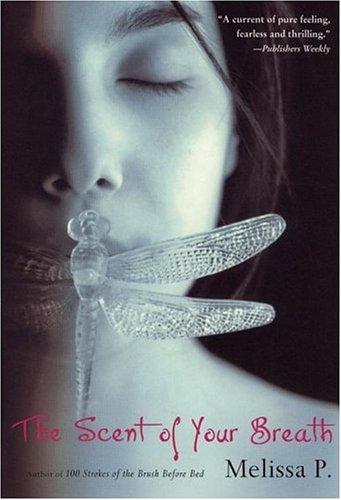

‘The Scent of Your Breath’ is described on its cover blurb as the sequel to ‘One Hundred Strokes Before Bed’. The debut is the fictional memoir of a teenage girl searching for love and prepared to do anything to find it, the sequel finds the teenager now a famous writer living in Rome with her kind compassionate lover, Thomas.

‘The Scent of Your Breath’ is described on its cover blurb as the sequel to ‘One Hundred Strokes Before Bed’. The debut is the fictional memoir of a teenage girl searching for love and prepared to do anything to find it, the sequel finds the teenager now a famous writer living in Rome with her kind compassionate lover, Thomas.

Told in the form of a dialogue to her mother, one would have expected this sequel to be a happier tale with the young girl at last at peace with her sexuality and content with her success and the wonderful lover who now shares her life. But this is not to be.

In this skimpy 118 page novel, the reader is taken through a confusing angst filled account of a girl’s life. She is portrayed as wise, yet still a child and emotionally disturbed enough to see and hear traumatised beings from another place. Her partner patiently deals with her inconsistent sexual demands and displays of passion, love and loathing. And all the while she shares their most intimate moments with her mother who the teenager addresses in an adoring and obsessive manner.

The chapters are short choppy pieces which flick back and forth through the deluded girls memories of childhood events and past affairs with faceless, nameless men. She often hints at incestuous abuse but refuses to let the reader in on the truth which is where the book fails and veers towards self indulgence.

As the story progresses the main character slips between reality and fantasy. Ghostly visitations encourage her self destructive behaviour and eventual mental breakdown and attempted suicide. Mental illness in young girls is not an original theme and near the end of the novel the similarities with Plath’s ‘The Bell Jar’ are hard to ignore.

The language in the novel is beautiful and poetic; it could almost be described as a narrative poem. But this poetic quality often leads the reader into dark corners, fumbling to find a deeper meaning in the prose. There are also a number of chapters which appear contrived and have no obvious relation to the narrative, for example one where the heroine refuses drugs could have been left out without harm to the overall effect.

However it is the rich language and stunning imagery that makes this book enjoyable to read, but although the writer has great poetic flare, the naïve style and contradictions prevents this becoming the masterpiece Plath produced.

Although I felt no pathos towards the main character, I did applaud one of the author’s acknowledgements at the end of this short book were she thanks – ‘all who hate me, because it’s thanks to them I love myself all the more.’