When police raided a lap dance club at San Dona di Piave near Venice the other day they found that the “dancers” were all under eighteen. The place was awash with drugs, and the gyrating “Lolitas” said they were ready for sex “with anyone we take a fancy to”, according to Il Giornale. “This”, said the paper censoriously, “is the Melissa P. generation”.

When police raided a lap dance club at San Dona di Piave near Venice the other day they found that the “dancers” were all under eighteen. The place was awash with drugs, and the gyrating “Lolitas” said they were ready for sex “with anyone we take a fancy to”, according to Il Giornale. “This”, said the paper censoriously, “is the Melissa P. generation”.

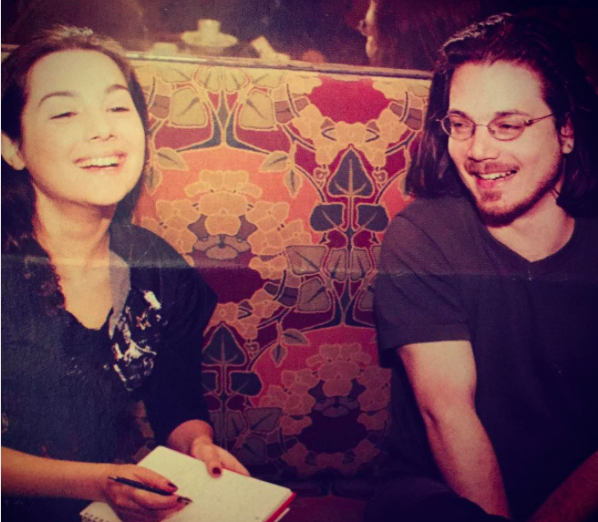

“Melissa P.” is Melissa Panarello. She looks like any other eighteen year old girl you might see in a gathering of students in a Rome cafe: pretty, petite, appealingly round faced, remarkably self assured, with an infectious giggle. When I met her she was dressed demurely in a long black dress with black ankle boots, with a minimum of make up and pale pink lipstick.

But Melissa is a media star in Italy, which is simultaneously appalled and fascinated by her. For what has thrust her into the limelight – much to her surprise, or so she says – is the graphically detailed diary of her teenage sex life, beginning at the age of fourteen, when she explores her own body in front of mirrors, followed by the loss of her virginity at fifteen and an astonishing variety of sexual experiences thereafter, including lesbianism, phone sex, Internet sex, group sex, anal sex, sado masochism, affairs with married men, you name it.

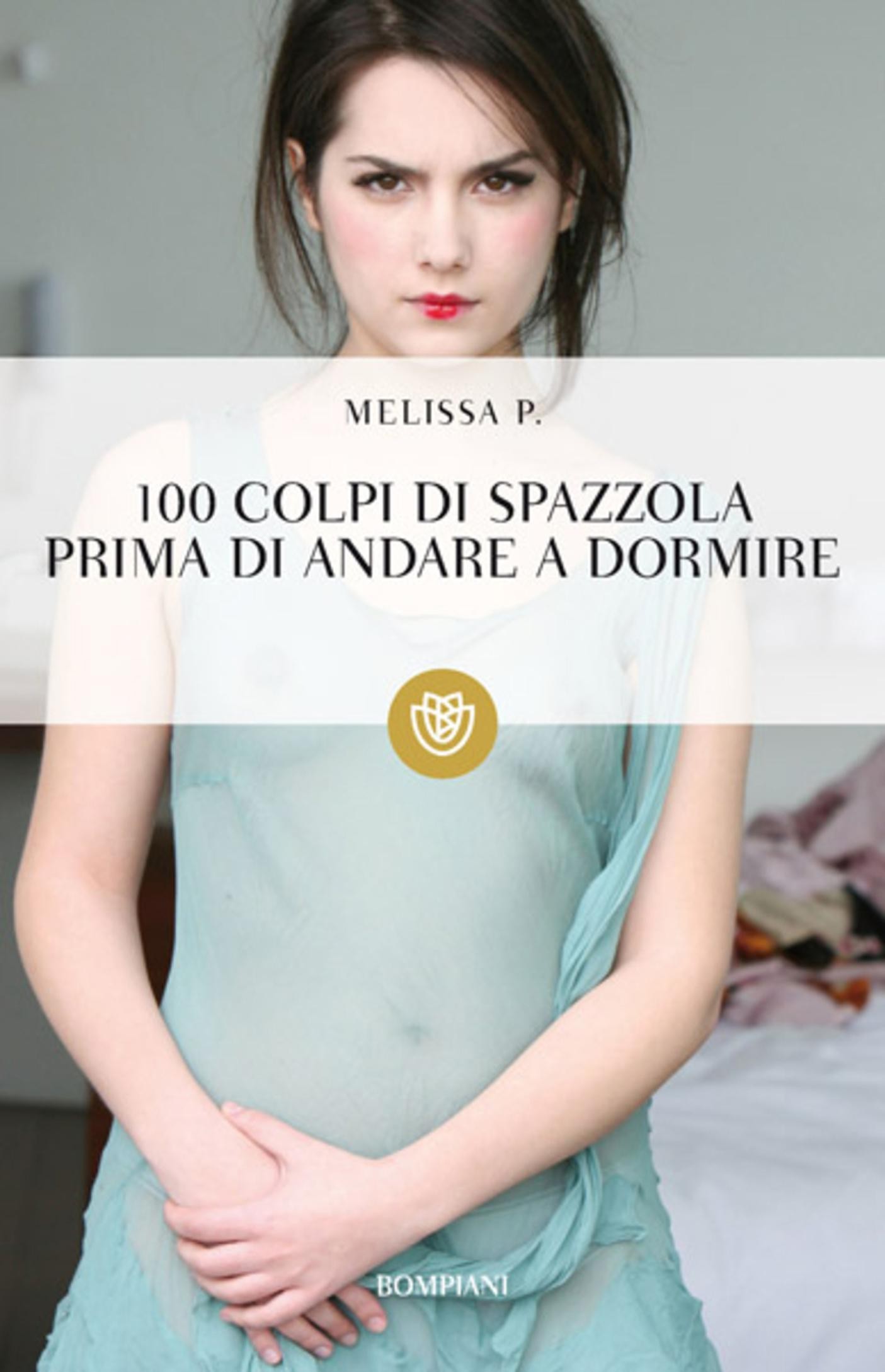

The shock waves of this self revealing schoolgirl’s confession – if that is what it is – are still reverberating in Catholic Italy, where such frankness is unusual, to put it mildly. The book, “One Hundred Strokes of the Hairbrush Before Going to Sleep”, was originally published last summer as by “Melissa P.” to disguise her identity, since she was then under eighteen. Interviews were conducted by e-mail only, and no photographs of her were allowed.

But all that has given way to celebrity status. The book has sold a stunning 650,000 copies in a country where a book which sells 20,000 is a bestseller. The publishers, a small firm called Fazi Editore set up just seven years ago, are still stupefied by their coup. According to Thomas Fazi, son of the founder, Elido Fazi, the firm’s previous best selling book was “The Heart Is Deceitful Above all Other Things”, teenage tales of low life in the American South by the precocious American writer JT Leroy. It sold 30,000 copies.

“In Italy you are doing well if you sell 5000 copies” Fazi says. Melissa’s diary had needed “hardly any editing at all. A bestselling author like Stephen King has seven editors”. The suspicion however expressed in some Italian papers – those that have reviewed the diary, that is, as opposed to those which have so far loftily ignored it – is that “One Hundred Strokes” was not written by Melissa at all, or perhaps only partly written by her. It reads, they say frankly, like a work of pornography. The encounters she describes take place in flats and cars, but also in a series of villas which are mysteriously empty, and to which her lovers always seem to have access.

When I put this to Melissa, who has heard the charge many times, she gives me a cool, appraising stare, and flicks back her hair. “Look – when someone writes a book they tend to write about what they know. I wrote it to understand myself better, to come to terms with what happened to me. ” She simply sent off an e-mail to the publishers from Catania in Sicily, her home town, with an account of her explicit diary, and “they thought I had something”. She merely expanded the experiences, which took place over a year, into a two year diary.

“I really don’t know how to respond to the accssation that my book is a fake” she says. “It’s just insulting. Any author would feel humiliated.” She admits there are “element of fantasy” in the diary but won’t say which bits are true and which not. The “Melissa” of the diary, she says, is “more or less “the real, autobiographical Melissa, but semi-fictionalised: when five young men make love to her in a room above the Catania fishmarket, the diary Melissa is disgusted, but the real one – she says – was not.

“I think of my book as erotic, not pornographic” she says .”But women are attracted by pornography as much as men -it just takes courage to admit it”. There are some non sexual passages in the book: she describes for example the heat and humidity of seaside Catania, beneath the smouldering volcano of Mount Etna, and the cafes where its young people gather. The tone is a mixture of gushing adolescent romanticism and anxious self doubt. There are poetic passages: the “Hundred Strokes of the Hair Brush” refers not to spanking but to fairy tales told to her by her mother in which the princess brushes her long hair before going to bed.

But mainly there is sex. She talks bluntly about orgasms and sperm, but rather oddly refers to her private parts coyly as “My Secret” (Mio Segreto). She parades in high heels and sexy underwear and runs through a variety of partners in a haze of alcohol and marijuana (no hard drugs are mentioned), moving from “Daniele” (the names have been changed), a schoolboy with “dazzling white teeth and strawberry flavoured breath”, who takes her virginity when she is fifteen, to Roberto, “my presumptuous angel”, who has a steady girlfriend and therefore meets her clandestinely.

When she turns sixteen Roberto introduces her to group sex, for which she is blindfolded, and from which she emerges with “sad eyes and a violated mouth”. Then comes Ernesto, whom she meets first in a chat room and then in real life, and who likes dressing up in women’s underwear; Letizia, her lesbian lover, also met on the Internet; Fabrizio, a married man for whom she acts out Miss Whiplash sado masochistic fantasies; and Valerio, her mathematics teacher, who calls her his “Lolita”, (she claims not to have read Nabokov’s novel), and takes her to an orgy in a villa.

But then, finally – a point missed by some reviewers and interviewers, perhaps because they did not plough through the book to the end – she meets “Claudio”, her Mr Right, who senerades her with a guitar while she is on her balcony, tells her he has “never met a girl like you before”, and teaches her about love and respect. Sex, she discovers, is meaningless without love. So is “A Hundred Strokes” in the end a kind of morality tale?

“In a way, yes. I’m not trying to convey a message – it would be absurd for a girl as young as me to presume to lecture people. But the story does have a moralistic ending, about finding oneself and finding love in the process”. So does “Claudio” really exist, or is he a Prince Charming fantasy? “Oh he certainly did exist. I say did because it came to an end, as things do, and I have moved on to other relationships. But I learned a lot, and Im still looking for love”.

Her school chums, Melissa says, were not surprised when the book came out because she had already shown them the draft text at school – “though not in the classroom” she adds, in gale of giggly laughter (she laughs a lot). Her parents however were shocked at first, as well they might be – not just because of the revelation of what she got up to when they thought she was just hanging out with other girls, like her best friend Alessandra, but also because they are depicted as remote and indifferent, too busy with their business (they run a clothes shop) or watching TV to ask her why she stayed out till five in the morning.

Her mother threw her first draft away in disgust after she found it, even though Melissa told her it was an invention, “which wasn’t true”. Her parents have since come round and are “proud of me and my success”, she says. “The picture of my parents is not exactly rosy, I know. But I didn’t want to write too much about the exterior world, my family circumstances and so on, I wanted to write about my interior world. My mother and father gave me remarkable freedom, really, they gave me a lot of space and never asked too many questions.” She claims she is now much closer to her mother, who at first accompanied her to interviews, but now lets her get on with it.

Melissa is planning a book of short stories next, and Francesca Neri, the Italian actress, is to produce a film “based on” the diary. The old taboos of Catholic Italy, Melissa says, have fallen, and her book is a symptom of this. “It’s also a worldwide phenomenon – there are books similar to mine by girls or young women in places like Russia. Women are finding the courage to tell the truth after years of hypocrisy”. So is she a post feminist, or perhaps a post-post feminist? For the first time, the giggling stops. “Look, I can’t stand all this feminist and post-feminist nonsense. My mother is a feminist, far too much so in fact, and I want nothing to do with it”.

Why not? “Because feminism is all about women feeling they are victims, and it’s just stupid. It pains me. My mother’s generation goes on and on about being victims of men, victims of this, victims of that, victims of life itself. But I don’t feel I’m a victim of anyone or anything. Women have the same right to respect and choice as men. It’s a question of taking charge of your own destiny – and that is what I have done. I have mapped out a plan of action for my life, and I am following it”.